15 minute read

Why Antichamber Is One of The Best Puzzle Games Ever Made

Back in 2013 Antichamber came out and I was hyped. I bought the game in late 2013 and played through some of it, but I distinctly recall I never finished it. Now, in 2024, I’ve played it again, this time to completion. Though given that it’s been over 10 years in-between, it’d be more accurate to say that I played it for the first time, because I genuinely couldn’t remember almost anything about the game other than the basic idea of it being a first-person cube–puzzle game. The fact that I effectively played it blind has only made me want to share my experience more, because I was blown away by this game—I seriously didn’t recall it being so amazing.

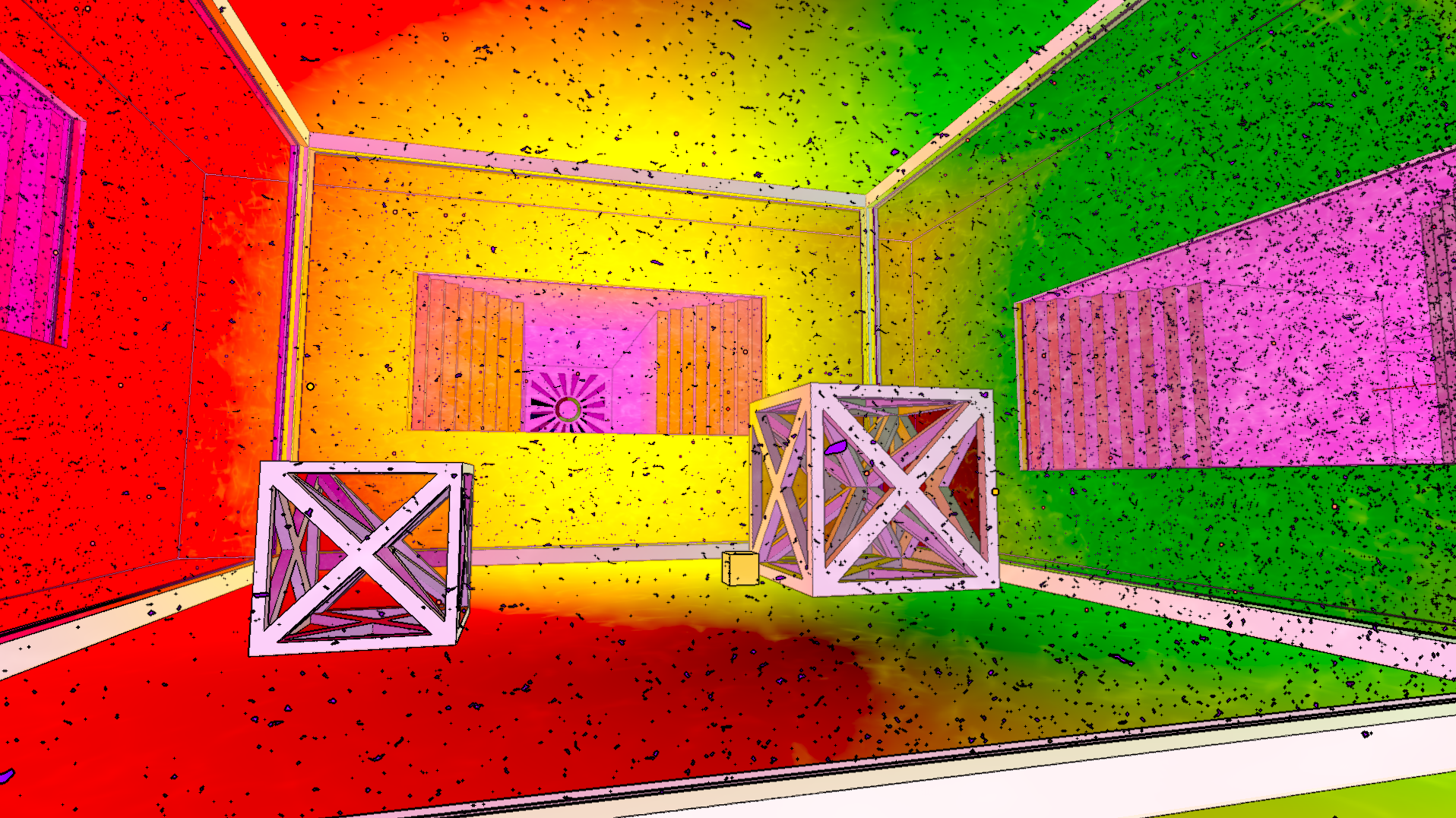

This room shall have all the colours

Categorizing Puzzle Games

Before describing why I think Antichamber is so special I’d like to briefly describe my general experience with puzzle games, in order to effectively compare and contrast.

I think the Puzzle Game genre is somewhat hard to qualify—ultimately all games involve some aspect of problem-solving, and Puzzle Games supposedly place an emphasis on the puzzle solving as opposed to anything else. But how much emphasis does a game need to place on puzzle solving to be classified as such? Given the axis of Sudoku ↔ Portal ↔ Half Life 2, I believe most would firmly categorize the first two as puzzle games but the third as an FPS. However, puzzles are a key feature of Half Life 2’s gameplay and in many instances take the spotlight. With that in mind, I’ll describe some games that I categorize as puzzle games.

I’ve played a fair share of puzzle games throughout my life, both in terms of quantity and in terms of breadth, and I would broadly group them into the following categories:

- The mechanically extremely simple. This would include games such as Sudoku or Minesweeper. There are very few rules, and conceptually the game is simple to grasp. There is one solution per board/level. The difficulty of these games comes from limiting the pre-filled information, so that you have to work out more yourself.

- The endless tile-based. A game such as Dorfromantik is based around the idea of having a limited set of tiles that you can place almost anywhere. The primary goal is to get as far as you can—there really is no final state of the board and definitely no such state as solved. There are, comparatively with ①, much more rules; different tiles next to one another provide bonuses, there may be secondary or tertiary goals that give bonuses, et cetera.

-

The endless free-form. Games such as Mini Metro or Mini Motorways.

These sorts of games share a lot with ② but they are not based on tiles with placement

rules. Rather, you can connect and place

stuff

anywhere you want. The Mini games, whilst having the same primary goal to get as far as you can, are simplistic in gameplay and have little else; there are no bonuses or secondary goals. -

The

simulation

. These are games that attempt to simulate something, for a loose definition of simulate. The rules are often based on physics or logic and each level has a solved state. However, there are many solutions which score higher or lower on perpendicular axes of measurement. For example, in Poly Bridge you have to build bridges to allow vehicles to cross. If the vehicles cross, the level is completed, but you could solve a level using a lot of money and designing a very rigid structure, or using little money with a bridge that almost breaks. Another example would be Zachtronics titles, which are effectively gamified programming challenges with an efficiency ↔ space ↔ cost trade-off. - The world manipulation. These games involve manipulating something in a (usually 3D) world, often based around the idea of rooms (in the literal or figurative sense), where you have to solve the room to progress to the next. These would be games like Portal, Superliminal, The Witness, and Antichamber.

Puzzle Games As A Scientist Simulator

The first four categories are mostly about solving puzzles using shown and/or explained mechanics. Whether it’s through dryly written rules or a more interactive walkthrough, you first learn the rules of the game, and then you have to employ those rules to solve the puzzles.

However, the fifth category is different. I once read someone describing these types of games as

being a scientist, trying to understand the foreign [game] world.

I think this

description aptly captures what makes these games unique: the game doesn’t tell you what the

rules are; instead, you have to figure them out yourself.

Often the game will introduce mechanics slowly to give the player a chance to learn and discover them without becoming lost or overwhelmed. Let’s take Portal as an example. The first puzzle doesn’t even have the portal gun. The game first introduces you to the idea of portals (but doesn’t give you the power to manipulate them), then introduces you to cubes and the physics-based gameplay, then gives you the ability to shoot only one portal, and finally gives you the full portal gun. In the case of Portal 2, this is further expanded by introducing gels later on in the game, and in a similar fashion—one gel at a time, until all gels are used in one level. This design both naturally introduces gameplay elements without forcing dialogue or written explanation, but also gives the player the satisfaction of figuring things out for themselves.

The way this design methodology can backfire is if the player struggles to figure things out.

They can become frustrated and quit because they missed something that was, in hindsight,

obvious

. Some games, like the Portal series, have a lot of handholding.

Meanwhile, The Witness is infamous for its latter puzzles having a very steep

difficulty curve.

Taking This To The Logical Extreme

Antichamber takes this idea far beyond what most other puzzle games in that category offer, and it does it by subverting most expectations you have as a gamer with regard to movement and interaction with the world.

To start of, the world of Antichamber at a glance is extremely bare, but this already is a subversion of expectations because a blank, empty wall may not in fact be blank nor empty. Did you think that walls are solid and impenetrable? The game says no—some walls disappear as you attempt to walk into them, revealing a hidden passage. That solid-looking floor can disappear under your feet and reveal an elevator which deposits you to a chamber below. A door may appear to close just when it comes into your field of vision, every time, yet if you walk backwards without looking at the door it will let you pass through. Or attempting to walk into a big hole in the ground will reveal a walkway that constructs itself around your feet as you cross.

The game consists entirely of rectilinear rooms and chambers connected by

corridors—equivalent to what the very first FPS games were doing—yet it manages to

surprise you at almost every turn. Every time you think you now understand how this world

operates, the game throws something new and unexpected, and you say Huh?

These mechanics

encourage the player to explore the world in a very hands-on manner. Numerous times I just ran

into walls and they were in fact solid walls, but on the odd occasion I would run into a wall

and it would reveal a secret, and I felt accomplished as if I had discovered something very

important.

The Non-Euclidean–ness

The aspect that Antichamber is famous for is its non-euclidean geometry.1 If the previously described shenanigans weren’t enough, the non euclidean geometry makes the world ten times more confusing.

This game has all sorts of non-euclidian tricks. Some of them are limited to act as interesting visuals—they create a unique experience viewing and interacting with them but don’t affect traversal through the world—but most do affect how you traverse the map. There are sections that loop infinitely, unless you backtrack and break free of the loop. There are areas that seem to loop in on themselves without intersecting, defying spatial intuition. Many areas can be reached from many places. Some shortcuts only work in one direction of travel but not the other. Geometry can even change depending on where you’re looking and reveal spaces in what were previously solid walls.

It’s this non-euclidean geometry that elevates this game above others. When basic navigation becomes a challenge and the map is a confusing mess, it’s so easy to think you know the way from A to B yet get lost anyway. Many times the player won’t remember clearly how to get somewhere; they will attempt to reach a location from another known location but fail, retry again and maybe succeed. Maybe you know how to get to B from X or Y, but you need cubes for a puzzle at B, and neither X nor Y have cubes, so now you need to pick a different starting location and figure out how to path find anew. Over time the player will memorize some routes through the map, and become more confident in the commonly traversed areas, but throughout the entirety of the game the player must find unexplored areas.

This unusual geometry encapsulates the trying to understand the world

aspect. It is

confusing but ultimately rewarding. Your first play through may take 7 hours, but the second

play through 20 minutes.

Puzzles Within Puzzles

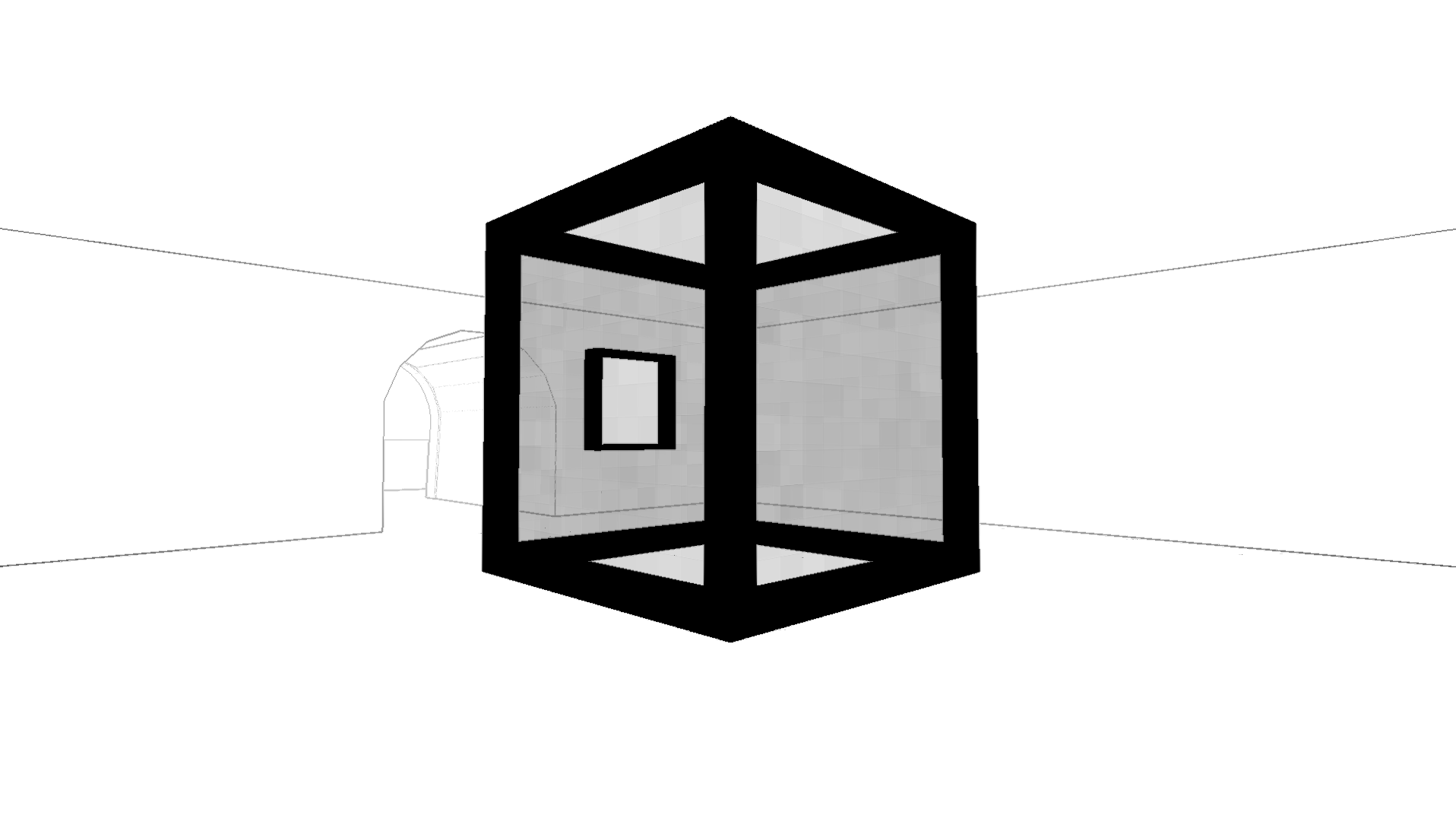

Non-euclidean geometry takes the centre stage, but Antichamber also has more traditional puzzle mechanics within: little cubes that you can manipulate.

These cube puzzles revolve around having to spatially manipulate them, using a gun. There are multiple tiers of guns with ever increasing capabilities, and different cube puzzles require different tiers of the gun to complete. Antichamber, trying to be as minimal as possible, omits detailed explanations of the capabilities of each gun whenever you unlock one, instead opting for simple decals placed on the walls that show which mouse buttons to press. These are great at giving you a basic idea of how the rules work, but they also omit a lot of subtle details about how the guns work and in what ways you can manipulate the cubes.

What this results in is that you, as the player, end up solving some cube puzzles quickly and without trouble, whilst other puzzles will leave you scratching your head, questioning whether they can even be solved at all. For some particularly difficult puzzles, I needed multiple attempts over many gameplay sessions because I just couldn’t figure them out. Just as with the non-euclidean map, you have to figure things out yourself rather than relying on the game to tell you.

A Harsh World

Aside from the excellent, and confusing, puzzle mechanics, Antichamber is unique in its visuals too.

The world is starkly black and white for the most part, with a touch of colour here-and-there. The rarity of colour serves multiple purposes; it makes certain rooms of the map more memorable; it guides the player into exploring important areas; it creates a contrast. Equally, sound is also rarely but carefully used throughout the map. It is used to give hints, but also modifies the atmosphere. It is also used to create momentary confusion.

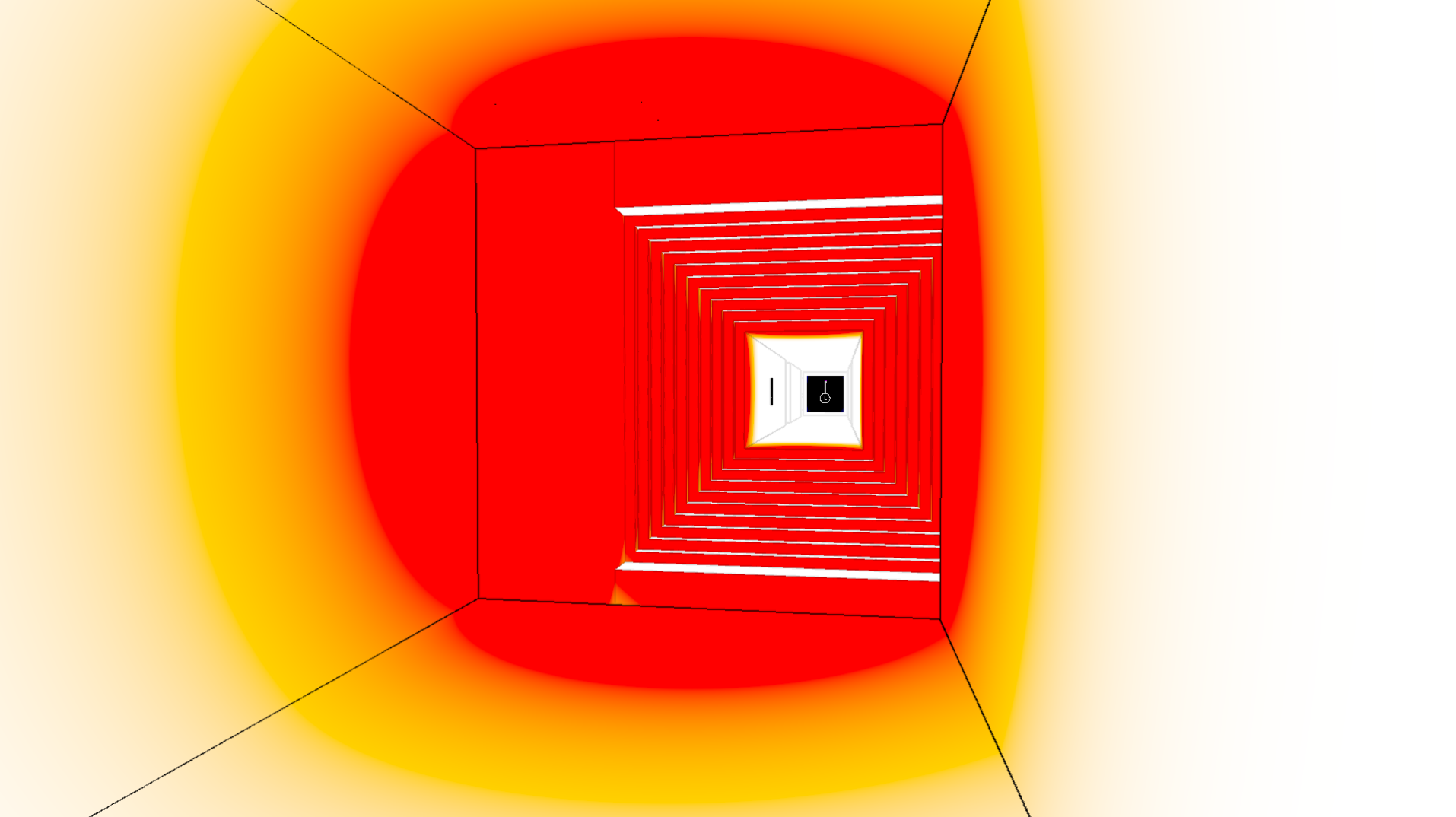

Red Room, which is a common travel destination. Recognizable by its absolute redness.

My perception of this world would be generally described as austere. The game felt very clinical and the world devoid of any life. A lot of the time I felt slightly on the edge, constantly unsure what was about to happen. But when I would come into a particularly colourful room, or hear the chirping of birds fade in, suddenly the harsh atmosphere was lifted and the world felt bright and alive. As with everything in this game, I am unsure of the deeper meaning behind this artistic direction, if there is one.

But the world isn’t only hard in its appearance; it’s harsh in the mind too. The game has no menu per se, but it does have a main room you can always come back to. When you start a new game you’ll notice a timer that starts counting down immediately. Obviously, this creates the perception that you have a limited amount of time to complete the game, before…—what exactly, you don’t know. But it’s a trick, because the timer can run down to 00:00:00 and absolutely nothing will happen.

There are multiple doors that tease the player with secrets, but secrets they do not hold. You

may come across a door labelled Under construction

, but to get to it, you must first

solve some puzzles. Naturally, you assume that the title is a joke, a trick of sorts. In

actuality however, you complete the puzzle which involves non-trivial effort to stand in front

of the door that won’t open. Did the developer plan to have further rooms but ran out of time,

or was it a ploy from the beginning?

Not only does this game have a brutal aesthetic that can be described as

the opposite of homely,

it plays mind games with you at all times, whether it’s through

the non-euclidean geometry or other tricks. The word harsh is truly fitting to describe

this game’s presentation.

The Ending

For a game with no story, background context, or dialogue, Antichamber has a surprisingly grand ending. Most puzzle games don’t have an ending, and the ones that do have relatively sane ones, but just like everything else about Antichamber, the ending is truly bizarre.

You finally almost reach the mystical black cube, but it starts running away and you have to chase it. There’s a series of linear non-euclidean puzzle rooms, and as you travel through them the black cube is always just at the edge of your vision. The music really picks up into a full, rich sound that both suggests excitement but also urgency, though as is with this game, the urgency turns out to be an illusion. The rooms are quite colourful too, which builds up the sense of importance. Ultimately you end up in the final puzzle room, which you traverse in one direction unstopped until you reach the cubes, and then have to travel in reverse by completing the cube puzzles. Compared to the other cube puzzles, this one is unique—it shows you every puzzle you will need to solve before you have a chance to solve it.

Finally, you reach the black cube and suck it up into your gun, turning it black too. In the process, you seem to suck up the entire world into the cube, leaving you alone in a colourless, stark white room. As you exit the room you find yourself on a floating path. You can see the path, the room you just left, massive towers in the distance, all floating in space; the towers seem to go on forever.

As you explore this space, you notice that the towers seem to stretch to infinity, literally. You jump down, and down again, and everything seems the same each time. You walk around more. You identify a room that looks like the starting room, but surely it can’t be—after all, you didn’t backtrack in your steps. The only other thing you’ve seen is a platform that is definitely not the starting room, but you can’t seem to find a path leading to it. You continue wandering more. In the distance, you notice a landscape feature that looks just like the one you’re standing at right now. You traverse more and find yourself back in the same spot. Again and again. You jump off a ledge and as you fall, you see the world repeating. You realize you are in a three-dimensional torus.2

Final Words

Antichamber is a peculiar game. It presents itself visually and audibly unlike any other game. Subverts expectations unlike any other game. It utilizes mechanics that are almost non-existent as far as games are concerned. Doesn’t give answers to any of the multitude of questions you will have. It just drops you into a strange world, and gives you full control to explore it as far as you wish.